Life can so quickly change. Bend the wrong way, trip, foolishly lift something the wrong way and suddenly, our lives change direction as we cope with rehabilitation and pain management. Some time back I walked into a branch at eye level in the entrance to the local supermarket and I spent the week visiting doctors and specialists wondering if my sight was going to be restored.

Fortunately it recovered and I can see well enough to write this article. Accidents play a big part but it seems that at times we are hell bent on our own destruction. I have had the misfortune of seeing a number of professional musicians who have played since their early childhood and have had to stop playing their instrument in their 20’s, retrain for other employment and live the rest of their life with a level of pain from their injuries. It wasn’t a chance accident that caused it, but rather a lifetime of repetitive strain on the body, ignoring the pain until it reached the point of no return.

Some years ago I watched a shared double bass recital where two professional musicians each played a ½ hour solo composition. Both musicians played at the highest musical standard, pieces of equal difficulty. At the end of the performance one musician was a lather of sweat and looked like he had run a marathon and the other had a small bead of perspiration but looked like he could go for another round easily. As a student who raised extra cash doing labouring jobs, I was very impressed with the no sweat approach.

Our approaches to the way we play bass are passed down generation to generation and drilled into the keen student until we can’t possibly hold our instrument or bow any other way. Good habits, and potentially harmful habits, all passed on from generation to generation from master to student.

One person who escaped this loop of instruction is François Rabbath. Growing up in Syria he had no teacher and had to invent things for himself. What evolved was a different way of approaching double bass playing that used his body weight and balance rather than muscle effort to play. Both of the performing musicians mentioned above had studied with some of the greatest bass teachers of our time, however the performer who made it seem effortless, had been relearning his technique from the ground up with Rabbath.

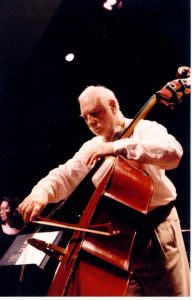

François Rabbath has spent a lifetime with his bass. He began playing at the age of 13, (the family band needed a bass player and he was chosen) and now at 83 years old, he continues to practise every day and perform frequent concerts around the world. Being a double bassist has not only allowed him to travel and earn a living doing what he loves, but it has also kept him fit, and in better health than many people half his age. He suffers no back or shoulder pain and while many people his age are becoming more restricted in their activities, his technical wizardry on the bass seems to grow each time I see him. Graeme Strahle wrote in his review for The Australian in 2003

“Rabbath is a wizard on the double bass, fingers flying with apparent freeness all over the fingerboard. Undeniably he is a virtuoso, making this sometimes intractable, gruff old instrument dance with the grace and delicacy of a violin. And that’s where his uniqueness lies: it is the apparent effortlessness of his sound, a product even more of his extraordinary fluid bowing action, that blows away all notions of the bass being a leaden object requiring brute force to muscle into action. Quite simply Rabbath is a self made phenomenon with no parallels in the modern era ”

Robert Battey from the Washington Post in a review of Rabbath’s concert writes “This self-taught artist remains one of the most fascinating and charismatic string players before the public. Although he suffered a fall that affected his left hand just before the concert, Rabbath played for 80 minutes without intermission, running through his many signature works, written by or for him, including Frank Proto’s pyrotechnical Paganini Variations. His own pieces are “world music” in the best sense, blending his Middle Eastern heritage with the style of his earlier collaborators, Michel Legrand and Charles Aznavour.

Rabbath’s bow technique is the equal of any violin or cello soloist, as he made clear in “Chasse à Cour,” tossing off bariolage, flying staccato, jete and every other trick in the bowing arsenal.”

“When we want to attain high proficiency we ask a continuous and prolonged effort of the body which, if we are not careful, causes it to become deformed over the years.”

François Rabbath

Bass players, like everybody, are susceptible to strains and injuries if they do not employ sensible posture when they play. Their backs, necks, shoulders, and arms are particularly sensitive, and the wrong posture for a sustained period can leave them in too much pain to play, permanently. Perhaps a good test of where you are heading would be to ask your teacher/mentor or your teacher’s teacher about the aches and pains they suffer. Take a look at how they perform in their seventies. Are they pain free and still enjoying creating music on their instrument?

If not – figure out if it was an accident or whether it is a lifetime of poor posture or technique.